In addition to my acoustic playbacks and monitoring through the northwest (California and Oregon), I also collected some data through bat captures. After going through the permit application process, multiple emails back and forth between California Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists and more emails, I was finally permitted to handle bats for my project starting in late July.

One of the major drawbacks of my current protocol is the inability to determine individual responses to bat social calls. While I can estimate general activity before, during and after social call playbacks, I am unable to determine more specific details about an individual bat, such as species, sex or age. By adding a capture component to my research, I hope to be able to draw more detailed conclusions about how bats respond to social calls.

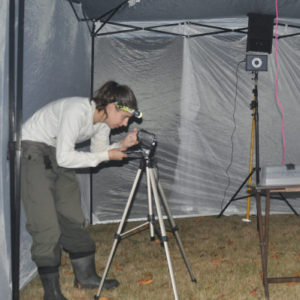

Testing bat responses to social calls require a more controlled environment, where the bat won’t simply just fly off. I needed something easily assembled in the field, easily transported and not too expensive. Turns out tents used for tail-gating and outdoor meals are the perfect solution: easy assembly, with mesh panels available to keep insects out (in my case, keep bats in). The more research I do, the more I realize how everyday objects can be hacked or adapted for wildlife research!

Bats were captured from local foraging areas, such as Benbow Lake State Recreation Area, Headwaters Forest Reserve and forest land owned by Green Diamond Resource Company. Initial capture attempts were focused on Green Diamond land, but with low capture rates I investigated other locations. The large number of bats at Benbow Lake State Recreation Area and the lack of water due to California drought meant easy pickings when it came to bat captures. One net over a puddle of water caught over 20 bats in about 20 minutes!

Following capture, bats were processed using usual methods, measuring forearm and weight, and determining sex and age. Both adults and juveniles were used in flight trials, and I hope to be able to compare their responses to social calls. A small bat box was mounted on either end of the flight tent, with cameras recording at both ends, supplemented by an infrared spotlight. The bat was placed on a table and confined by a small plastic bin over the top, and the tent was closed up. Using a pulley system, the bat was released at the same time as a call was being played. Sounds broadcast were either Myotis echolocation calls, Myotis social calls or Tadarida (free tailed bat) echolocation calls. Some bats were released without any call being played, to act as a control for how bats might behave in the flight tent. After letting the bat fly or crawl at free will in the tent for 5 minutes, the side of the tent was removed and the bat was allowed to fly out on its own. That process worked for the most part, though twice I had a second bat fly into the tent from the outside environment (which happened to only occur during social calls…promising!).

Armed with more infrared video data, I hope to be able to determine how bats are responded to these social calls. This will be done by measuring the amount of time the bat spent flying on different ends of the tent, as well as measuring behaviors such as circling, approaching or landing. Knowing demographic data such as sex or age makes it possible for me to compare behaviors between individuals and determine if all bats respond the same way to these calls.

Still lots to do and lots more video to watch, but I hope to have some updates soon!