Happy Bat-urday!

Spring seems to have come early to Humboldt, unlike much of the rest of the country where March is certainly coming in like a lion. Unfortunately, the past few weeks I’ve been cooped up in my office while the sun shined, wrestling with R code, manipulating graphs, eating lunch and dinner at my desk, typing away at the finishing steps of my master’s thesis.

I first decided I wanted to be a research biologist when I was 10, after finding the definition of “zoologist” in an encyclopedia. I knew I wanted to work with animals and this mysterious job seemed to fit me perfectly. As I grew older, I continued to explore wildlife biology and field research. As I searched for colleges, I was presented with images of students abroad, hiking mountains, playing with lions or smiling with eagles. As it turns out, there is way more to wildlife biology and research in general than you think about when you are 10 years old.

It reminds me of this meme that I’ve seen bounce around Facebook and other social networking sites in the past:

The last picture “What I actually do” has felt pretty realistic the past month or so. Field work is my bread and butter, it’s what makes me happy. Spending time connecting with the environment and getting to know the habits and behaviors of a study animal. Yet, it seems like for every hour of field data, is at least an hour in front of a computer, building code, running statistical tests, writing reports or theses. I don’t mean to sound petty, or like I am complaining. This is where wildlife biologists can make a real difference, disseminating their research among the public, sharing and exchanging information with colleagues, exploring new ideas and pursuing scholarship.

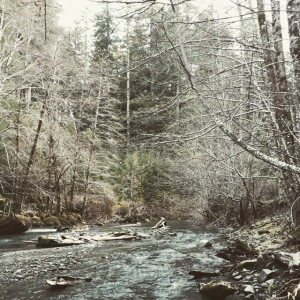

But, like I said, being out in the field is the biggest thrill of all. Last night, I got the chance to get my feet wet again (literally….we were walking in the creek all night) and remind myself why I chose this profession.

We headed back down to Humboldt Redwoods, where we had intensively netted last fall for migratory bats. Katelyn Southall, a wildlife student at Humboldt State is collecting data for her senior thesis on social calls in silver haired bats. The rains from earlier in February meant the creeks had been full and things had settled down enough for us to safely traverse in the water and setup nets.

The week of warm weather seemed to have been a boon for the bats, and was a boon for us. It was a migratory bat filled night, with multiple silver-haired bat captures, two hoary bats (the first of 2015!) and the uncommon western red bat.

And my pinnacle achievement for the night: using my fancy new smart phone to get a slow motion video of a hoary bat taking off into the night.

Science! It’s not a bucket of facts. It’s the process. The world can always use more scientists!